Researchers have found yet another family of malicious extensions in the Chrome Web Store. This time, 30 different Chrome extensions were found stealing credentials from more than 260,000 users.

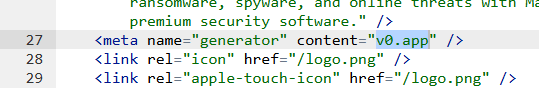

The extensions rendered a full-screen iframe pointing to a remote domain. This iframe overlaid the current webpage and visually appeared as the extension’s interface. Because this functionality was hosted remotely, it was not included in the review that allowed the extensions into the Web Store.

In other recent findings, we reported about extensions spying on ChatGPT chats, sleeper extensions that monitored browser activity, and a fake extension that deliberately caused a browser crash.

To spread the risk of detections and take-downs, the attackers used a technique known as “extension spraying.” This means they used different names and unique identifiers for basically the same extension.

What often happens is that researchers provide a list of extension names and IDs, and it’s up to users to figure out whether they have one of these extensions installed.

Searching by name is easy when you open your “Manage extensions” tab, but unfortunately extension names are not unique. You could, for example, have the legitimate extension installed that a criminal tried to impersonate.

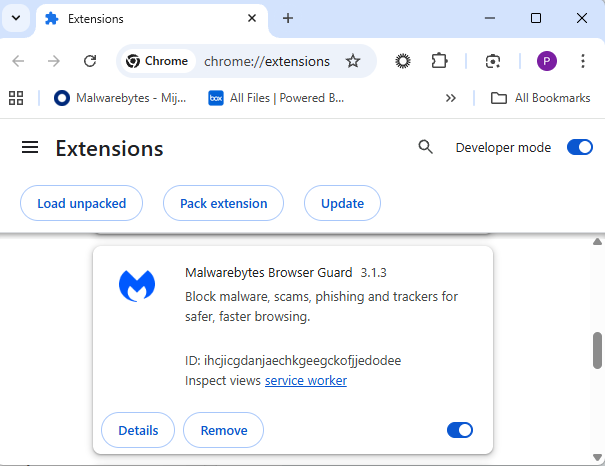

Searching by unique identifier

For Chrome and Edge, a browser extension ID is a unique 32‑character string of lowercase letters that stays the same even if the extension is renamed or reshipped.

When we’re looking at the extensions from a removal angle, there are two kinds: those installed by the user, and those force‑installed by other means (network admin, malware, Group Policy Object (GPO), etc.).

We will only look at the first type in this guide—the ones users installed themselves from the Web Store. The guide below is aimed at Chrome, but it’s almost the same for Edge.

How to find installed extensions

You can review the installed Chrome extensions like this:

- In the address bar type

chrome://extensions/. - This will open the Extensions tab and show you the installed extensions by name.

- Now toggle Developer mode to on and you will also see their unique ID.

Removal method in the browser

Use the Remove button to get rid of any unwanted entries.

If it disappears and stays gone after restart, you’re done. If there is no Remove button or Chrome says it’s “Installed by your administrator,” or the extension reappears after a restart, there’s a policy, registry entry, or malware forcing it.

Alternative

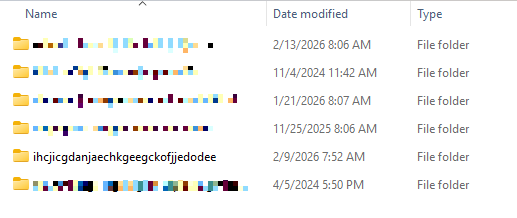

Alternatively, you can also search the Extensions folder. On Windows systems this folder lives here: C:Users<your‑username>AppDataLocalGoogleChromeUser DataDefaultExtensions.

Please note that the AppData folder is hidden by default. To unhide files and folders in Windows, open Explorer, click the View tab (or menu), and check the Hidden items box. For more advanced options, choose Options > Change folder and search options > View tab, then select Show hidden files, folders, and drives.

You can organize the list alphabetically by clicking on the Name column header once or twice. This makes it easier to find extensions if you have a lot of them installed.

Deleting the extension folder here has one downside. It leaves an orphaned entry in your browser. When you start Chrome again after doing this, the extension will no longer load because its files are gone. But it will still show up in the Extensions tab, only without the appropriate icon.

So, our advice is to remove extensions in the browser when possible.

Malicious extensions

Below is the list of credential-stealing extensions using the iframe method, as provided by the researchers.

| Extension ID | Extension name |

|---|---|

| acaeafediijmccnjlokgcdiojiljfpbe | ChatGPT Translate |

| baonbjckakcpgliaafcodddkoednpjgf | XAI |

| bilfflcophfehljhpnklmcelkoiffapb | AI For Translation |

| cicjlpmjmimeoempffghfglndokjihhn | AI Cover Letter Generator |

| ckicoadchmmndbakbokhapncehanaeni | AI Email Writer |

| ckneindgfbjnbbiggcmnjeofelhflhaj | AI Image Generator Chat GPT |

| cmpmhhjahlioglkleiofbjodhhiejhei | AI Translator |

| dbclhjpifdfkofnmjfpheiondafpkoed | Ai Wallpaper Generator |

| djhjckkfgancelbmgcamjimgphaphjdl | AI Sidebar |

| ebmmjmakencgmgoijdfnbailknaaiffh | Chat With Gemini |

| ecikmpoikkcelnakpgaeplcjoickgacj | Ai Picture Generator |

| fdlagfnfaheppaigholhoojabfaapnhb | Google Gemini |

| flnecpdpbhdblkpnegekobahlijbmfok | ChatGPT Picture Generator |

| fnjinbdmidgjkpmlihcginjipjaoapol | Email Generator AI |

| fpmkabpaklbhbhegegapfkenkmpipick | Chat GPT for Gmail |

| fppbiomdkfbhgjjdmojlogeceejinadg | Gemini AI Sidebar |

| gcfianbpjcfkafpiadmheejkokcmdkjl | Llama |

| gcdfailafdfjbailcdcbjmeginhncjkb | Grok Chatbot |

| gghdfkafnhfpaooiolhncejnlgglhkhe | AI Sidebar |

| gnaekhndaddbimfllbgmecjijbbfpabc | Ask Gemini |

| gohgeedemmaohocbaccllpkabadoogpl | DeepSeek Chat |

| hgnjolbjpjmhepcbjgeeallnamkjnfgi | AI Letter Generator |

| idhknpoceajhnjokpnbicildeoligdgh | ChatGPT Translation |

| kblengdlefjpjkekanpoidgoghdngdgl | AI GPT |

| kepibgehhljlecgaeihhnmibnmikbnga | DeepSeek Download |

| lodlcpnbppgipaimgbjgniokjcnpiiad | AI Message Generator |

| llojfncgbabajmdglnkbhmiebiinohek | ChatGPT Sidebar |

| nkgbfengofophpmonladgaldioelckbe | Chat Bot GPT |

| nlhpidbjmmffhoogcennoiopekbiglbp | AI Assistant |

| phiphcloddhmndjbdedgfbglhpkjcffh | Asking Chat Gpt |

| pgfibniplgcnccdnkhblpmmlfodijppg | ChatGBT |

| cgmmcoandmabammnhfnjcakdeejbfimn | Grok |

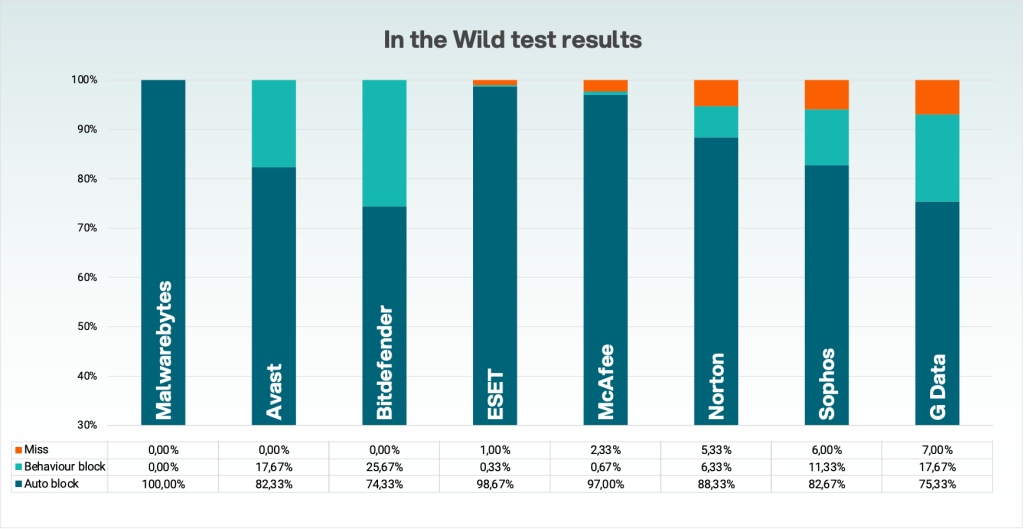

We don’t just report on threats—we remove them

Cybersecurity risks should never spread beyond a headline. Keep threats off your devices by downloading Malwarebytes today.