Google has issued a patch for a high‑severity Chrome zero‑day, tracked as CVE‑2026‑2441, a memory bug in how the browser handles certain font features that attackers are already exploiting.

CVE-2026-2441 has the questionable honor of being the first Chrome zero-day of 2026. Google considered it serious enough to issue a separate update of the stable channel for it, rather than wait for the next major release.

How to update Chrome

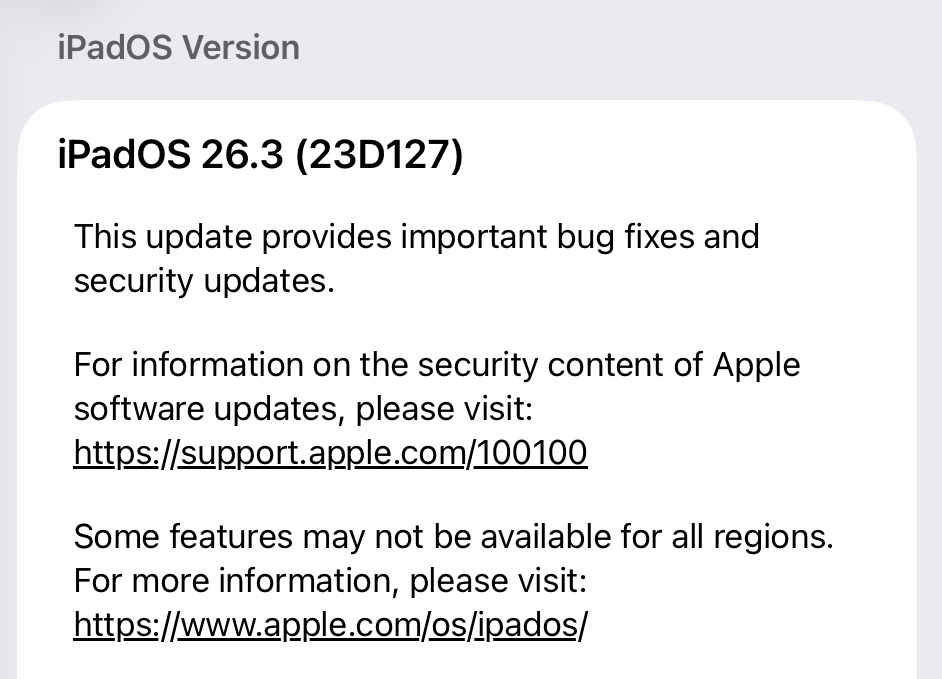

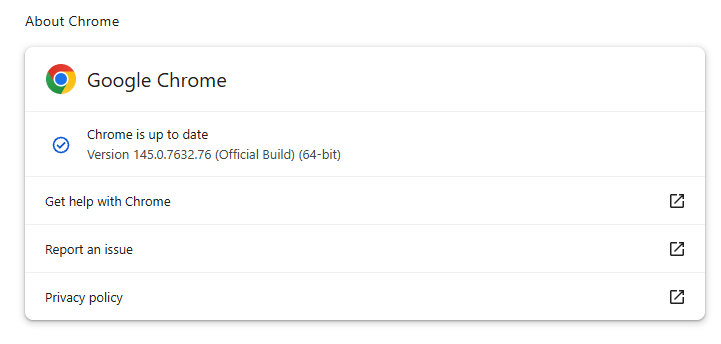

The latest version number is 145.0.7632.75/76 for Windows and macOS, and 145.0.7632.75 for Linux. So, if your Chrome is on version 145.0.7632.75 or later, it’s protected from these vulnerabilities.

The easiest way to update is to allow Chrome to update automatically. But you can end up lagging behind if you never close your browser or if something goes wrong, such as an extension preventing the update.

To update manually, click the More menu (three dots), then go to Settings > About Chrome. If an update is available, Chrome will start downloading it. Restart Chrome to complete the update, and you’ll be protected against these vulnerabilities.

You can also find step-by-step instructions in our guide to how to update Chrome on every operating system.

Technical details

Google confirms it has seen active exploitation but is not sharing who is being targeted, how often, or detailed indicators yet.

But we can derive some information from what we know.

The vulnerability is a use‑after‑free issue in Chrome’s CSS font feature handling (CSSFontFeatureValuesMap), which is part of how websites display and style text. More specifically: The root cause is an iterator invalidation bug. Chrome would loop over a set of font feature values while also changing that set, leaving the loop pointing at stale data until an attacker managed to turn that into code execution.

Use-after-free (UAF) is a type of software vulnerability where a program attempts to access a memory location after it has been freed. That can lead to crashes or, in some cases, lets an attacker run their own code.

The CVE-record says, “Use after free in CSS in Google Chrome prior to 145.0.7632.75 allowed a remote attacker to execute arbitrary code inside a sandbox via a crafted HTML page.” (Chromium security severity: High)

This means an attacker would be able to create a special website, or other HTML content that would run code inside the Chrome browser’s sandbox.

Chrome’s sandbox is like a secure box around each website tab. Even if something inside the tab goes rogue, it should be confined and not able to tamper with the rest of your system. It limits what website code can touch in terms of files, devices, and other apps, so a browser bug ideally only gives an attacker a foothold in that restricted environment, not full control of the machine.

Running arbitrary code inside the sandbox is still dangerous because the attacker effectively “becomes” that browser tab. They can see and modify anything the tab can access. Even without escaping to the operating system, this is enough to steal accounts, plant backdoors in cloud services, or reroute sensitive traffic.

If chained with a vulnerability that allows a process to escape the sandbox, an attacker can move laterally, install malware, or encrypt files, as with any other full system compromise.

How to stay safe

To protect your device against attacks exploiting this vulnerability, you’re strongly advised to update as soon as possible. Here are some more tips to avoid becoming a victim, even before a zero-day is patched:

- Don’t click on unsolicited links in emails, messages, unknown websites, or on social media.

- Enable automatic updates and restart regularly. Many users leave browsers open for days, which delays protection even if the update is downloaded in the background.

- Use an up-to-date, real-time anti-malware solution which includes a web protection component.

Users of other Chromium-based browsers can expect to see a similar update.

We don’t just report on threats—we help safeguard your entire digital identity

Cybersecurity risks should never spread beyond a headline. Protect your, and your family’s, personal information by using identity protection.