In the rapidly evolving world of artificial intelligence, the difference between a “good” result and a “game-changing” result often comes down to one thing: the prompt.

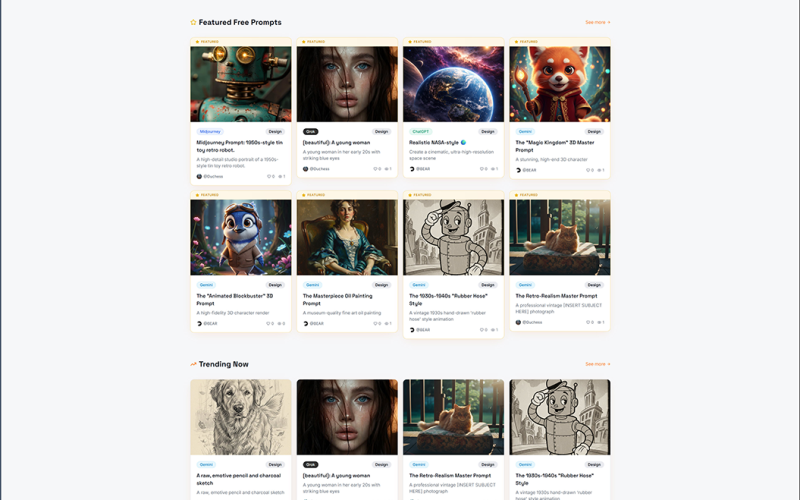

At Makologics, we are constantly seeking ways to make technology more accessible and efficient for our community. That is why we are thrilled to officially introduce our sister platform, AI Prompts Hive. Whether you are a seasoned AI engineer or just beginning your journey with ChatGPT, Claude, or Midjourney, AI Prompts Hive is built to be your ultimate digital command center for AI interactions.

What is AI Prompts Hive?

AI Prompts Hive is a centralized repository and social ecosystem designed specifically for the “Prompt Generation.” As AI models become more complex, managing the instructions we give them becomes a task in itself. Our platform provides a clean, intuitive space to discover, organize, and optimize these prompts.

Save, Organize, and Personalize

How many times have you written a complex prompt that worked perfectly, only to lose it in your chat history? With AI Prompts Hive, those days are over.

-

Personal Profile: Create a dedicated account to build your own private library of prompts.

-

Custom Categorization: Tag and categorize your prompts by use case—whether it’s for coding, creative writing, marketing, or data analysis.

-

Version Control: Refine your prompts over time and keep the best versions saved in your profile for instant access whenever you need them.

Share with the Hive (or Keep it Private)

One of the core features of the platform is the ability to choose how you contribute to the AI community:

-

Public Sharing: If you’ve cracked the code on a prompt that generates incredible results, you can share it with the “Hive.” By making a prompt public, you contribute to a growing database of knowledge, helping others achieve better AI outputs.

-

Community Discovery: Browse the public feed to see what other experts are using. You can find inspiration, “remix” existing prompts, and see what’s trending in the world of AI.

-

Private Vaults: For proprietary business logic or personal projects, you can keep your prompts set to private, ensuring that your unique “secret sauce” stays visible only to you.

Why Makologics and AI Prompts Hive?

At Makologics, our mission is to build intelligent solutions. By integrating the prompt-management power of AI Prompts Hive into our ecosystem, we are giving our users the tools not just to use AI, but to master it.

The best part? It’s completely free to get started. Join the hive today and start building your personal library of AI intelligence.

Visit www.aipromptshive.com and secure your profile today!