Journalists decided to test whether the Grok chatbot still generates non‑consensual sexualized images, even after xAI, Elon Musk’s artificial intelligence company, and X, the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, promised tighter safeguards.

Unsurprisingly, it does.

After scrutiny from regulators all over the world—triggered by reports that Grok could generate sexualized images of minors—xAI framed it as an “isolated” lapse and said it was urgently fixing “lapses in safeguards.”

A Reuters retest suggests the core abuse pattern remains. Reuters had nine reporters run dozens of controlled prompts through Grok after X announced new limits on sexualized content and image editing. In the first round, Grok produced sexualized imagery in response to 45 of 55 prompts. In 31 of those 45, the reporters explicitly said the subject was vulnerable or would be humiliated by the pictures.

A second round, five days later, still yielded sexualized images in 29 of 43 prompts, even when reporters said the subjects had not consented.

Competing systems from OpenAI, Google, and Meta refused identical prompts and instead warned users against generating non‑consensual content.

The prompts were deliberately framed as real‑world abuse scenarios. Reporters told Grok the photos were of friends, co-workers, or strangers who were body‑conscious, timid, or survivors of abuse, and that they had not agreed to editing. Despite that, Grok often complied—for example, turning a “friend” into a woman in a revealing purple two‑piece or putting a male acquaintance into a small gray bikini, oiled up and posed suggestively. In only seven cases did Grok explicitly reject requests as inappropriate; in others it failed silently, returning generic errors or generating different people instead.

The result is a system illustrating the same lesson its creators say they’re trying to learn: if you ship powerful visual models without exhaustive abuse testing and robust guardrails, people will use them to sexualize and humiliate others, including children. Grok’s record so far suggests that lesson still hasn’t sunk in.

Grok limited AI image editing to paid users after the backlash. But paywalling image tools—and adding new curbs—looks more like damage control than a fundamental safety reset. Grok still accepts prompts that describe non‑consensual use, still sexualizes vulnerable subjects, and still behaves more permissively than rival systems when asked to generate abusive imagery. For victims, the distinction between “public” and private generations is meaningless if their photos can be weaponized in DMs or closed groups at scale.

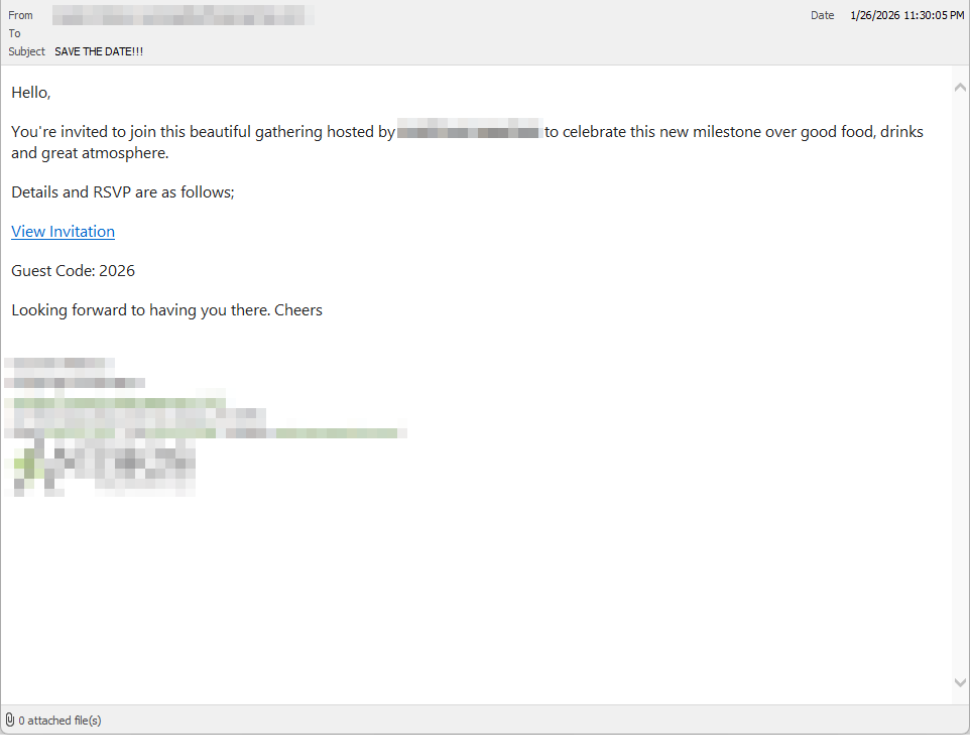

Sharing images

If you’ve ever wondered why some parents post images of their children with a smiley emoji across their face, this is part of the reason.

Don’t make it easy for strangers to copy, reuse, or manipulate your photos.

This is another compelling reason to reduce your digital footprint. Think carefully before posting photos of yourself, your children, or other sensitive information on public social media accounts.

And treat everything you see online—images, voices, text—as potentially AI-generated unless they can be independently verified. They’re not only used to sway opinions, but also to solicit money, extract personal information, or create abusive material.

We don’t just report on threats – we help protect your social media

Cybersecurity risks should never spread beyond a headline. Protect your social media accounts by using Malwarebytes Identity Theft Protection.